The Environmental Imagination

Dean Hawkes

Light Extracts

“Penetrate more deeply into the thinking of architects as they imagine the environment, the atmosphere, the ambience of their buildings. In most circumstances this involves establishing some kind of relationship between the elements of architecture, space, form, material, and mechanical systems for heating, ventilating, lighting. Together, these constitute the technics of the architectural environment, but technics or techniques or technologies alone, however important their role, fail to touch the central point. As I hope these essays go some way to show, the significant environmental propositions in architecture rest upon acts of imagination in which technics are brought to bear in the service of poetic ends.

“The essence of the environment that I am trying to capture must be directly experience; it cannot be completely discerned from images and verbal descriptions alone.”

“Steven Holl.”

Preface vi

“I only wish that the first really worthwhile discovery of science would be that it recognised that the unmeasurable is what they’re really fighting to understand, and that the measurable is only the servant of the unmeasurable; that everything that man makes must be fundamentally unmeasurable.”

“Andrea Palladio”

“Robert Smythson”

“The Villa Carpa”

“La Rotonda”

It is to be observed in making the windows, that they should not take in more or less light, or be fewer or more in number, than what necessity requires. Therefore great regard ought to be had to the largeness of the rooms which are to receive light from them; because it is manifest, that a great room requires more light to make it lucid and clear, than a small one: and if the windows are made either less or fewer that that which is convenient, they will make the places obscure, and if too large, they will scarce be habitable, because they will let in so much hot and cold air, that the places, according to the season of the year, will either be exceeding hot or very cold, in case the part of the heavens which they face, does not in some manner prevent it.”

Preface x-xi

“But, as practical science and its related technologies developed and found application in architecture from the end of the eighteenth century, this unity was eroded as reductive codification and specialisation took its place.”

Preface xi

“One foot of superficies of heating surface is required for every 6 feet of glass; the same for every 120 feet of wall, roof and ceiling; and an equivalent quantity for every 6 cubic feet of air withdrawn from the apartment by ventilation per minute.”

“Moving on to the twentieth century, the early decades saw the key work in establishing the foundations of the theory of environmental comfort. Here the objective was to establish connections between physical descriptors of environmental conditions, of heat, light and sound, within buildings and human needs.”

Preface xii

“It is now possible to design buildings in which quantitatively and precisely specified environments can be delivered by calculated configurations of building fabric and mechanical plant. But this success has, it seems, often been bought at a high price. My concern hinges around the emphasis of the quantitative as the principal object of environmental design, around precisely the conflict of the measurable and the unmeasurable expressed by Louis Kahn.”

“From the earliest times, humankind has sought to construct enclosures to offer protections against the extremes of heat, cold, wind and rain. Studies in the ethnography of architecture have shown how effectively the material resources of diverse places have been used to this end; they equally clearly show that such structures are quickly transformed to acquire meaning beyond mere practicality. Modern buildings continue to protect their occupants and their activities from the elements, but this is achieved for diverse and demanding ends by a vast and ever expanding array of technical means.”

Preface xiii

“The interaction of light and air and sound with the form and materiality of architectural space is of the very essence of the architectural imagination.”

“In Italian, the equivalent of the English environment is ambiente. This shares its roots with the French ambiance, translated as atmosphere in English, and the English use of ambiance (or ambience) that is defined as ‘the character and atmosphere of a place’ (OED), and atmosphere, in its non-scientific sense, is ‘the pervading tone or mood or a place’ (OED). In French, environment is milieu or environnement.”

“Indeed, Sir John Soane, in his lectures to the Royal Academy in London, used the presence or absence of ‘character’ to differentiate between the work of a ‘useful builder’ and that of an architect, ‘without which architecture becomes little more than a mere routine, a mere mechanical art.’”

Preface xvi

The environmental imagination

“Sire John Soane’s house”

“Charles Rennie Mackintosh achieved a different, but equally rich synthesis in his Glasgow buildings.”

Preface xvii

“Returning north, Sigurd Lewerentz brought a unique sensibility to bear in his response to the northern latitudes. His realisation of the potency of darkness and the human ability visually to adapt to it, as it ultimately realised at the churches of St Mark’s at Bjorkhagen and St peter’s at Klippan, is among the most remarkable acts of the environmental imagination.”

Preface xviii

“In experiencing architecture, Steen Eiler Rasmussen wrote with deep insight about the environmental qualities of architecture. His chapters on daylight, colour and sound remain among the most compelling texts to capture the ambience of buildings.”

“In memorable experiences of architecture, space, matter and time fuse into one single dimension, into the basic substance of being that penetrates consciousness. We identify ourselves with this space, this place, this moment and these dimensions become ingredients of our very existence. Architecture is the art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world, and this mediation takes place through the senses.”

Preface xix

“Willmert cites Soane declaring that in their houses the English must, ‘see the fire, or no degree of heat will satisfy’.”

Page 6

“As David Watkin shows, the ideas of Le Camus de Mezieres, most particularly in relation to the effects of light, la lumiere mysterieuse, lay at the centre of Soane’s architecture. The essential instruments in the realisation of these effects were the use of top-light, false or mysterious light and reflected light. John Summerson proposed that top-lighting, which Soane adopted as a matter of necessity in his work at the Bank of England, ‘becomes an essential of the style’ in the works of the so-called ‘Picturesque Period’ from 1806 to 1821. In addition, Soane consistently used colour to modify the effect of light. This was achieved in two ways. First, he used coloured glass directly to modify the tonality of the light that entered a building, false or mysterious light. Second, he made precise judgements about the colours that he painted internal surfaces and, thereby, controlled the nature of reflected light.”

Page 7

“These were almost exclusively top lit by an array of different forms of roof-light, no less than nine different types of top-light and one clerestory, that allowed precise calibration of the quantity, quality and effect of the illumination of the spaces below and their contents. The sky, even when overcast, is brightest at the zenith. This means that roof-lights such as those in Soane’s museum cast a strongly directional light vertically through tall narrow volumes. This dramatizes the space and gives the strongest possible modelling of three-dimensional objects that it illuminates. The well-known cross-section through the Dome, rendered by George Bailey, effectively represents Soane’s deep understanding of the physical distribution of light in architectural space (Figure 1.2). From autumn to spring these roof-lights receive no direct sunlight because of the overshadowing of the main body of the houses to the south. In summer, however, the roof is sunlit throughout most of the day, creating even more dramatic effects. With or without direct sunlight, the illumination of the effect of midday sun and red in the west facing roof-light in conformity with Turner’s colour symbolism, where crimson is associated with the evening.”

“Soane described the room in the following terms: The views from this room into the monument Court and into the Museum, the mirrors in the ceiling, and the looking-glasses, combined with the variety of outline and general arrangement of the design and decoration of this limited space, present a succession of those fanciful effects which constitute the poetry.”

Page 8

“When the shutters are closed, almost the entire south wall of the library is a continuous plane of mirrors. The drawing rooms are bright yellow and, in the south drawing room in particular, this enhances the direct sunlight from the south. As elsewhere, mirrors bring yet more sparkle to these rooms.”

Page 9 – image_01

“His lantern rooflights thereby cast their principal east and west light directly onto the upper parts of the long walls of the enfilade picture rooms and limit the penetration of high-angled south light (figure 1.5).”

Page 10 – Image_02

“It has been recorded that Soane ‘lit the ground floor and basement at night to exploit to the full the contrasts of light and shadow around the house and to create the maximum romantic atmosphere in which to appreciate the sarcophagus’. The lamps in the museum were concealed, placed close to mirrors or shaded with coloured glass and it has been suggested that some were placed inside the sarcophagus which would then have become itself a source of mystical light. The spectacle is further evidence of Soane’s acute awareness of the relation of light to space.”

Page 12

“Bibliotheque Ste-Genevieve, first floor, ground floor and basement plans. The basement plan, shows the layout of the heating and ventilating ducts that serve the upper floors.”

Page 14 – image_03

“This interpretation is supported and further developed by Neil Levine who wrote: The most obvious quality of the reading room is its openness and lightness. The deep, girding arcade, letting in daylight on all four sides, and acting as a brise-soleil for most of the day. One is constantly made aware of the passage of time by movement of the sun and of the fact that it is the skeletal iron construction that allows for this perception of the cycle of the day.”

Page 15

“Labrouste’s masterpiece is the Grand Magasin or stack room… The whole area was covered with a glass ceiling. Cast-iron floor plates in a grid-iron patter permit the daylight to penetrate the stacks from top to bottom… This hovering play of light and shadow appears as an artistic means in certain works of modern sculpture as well as in contemporary architecture… In this room – one never meant for public display – a great artist infolded new possibilities for architecture.”

“Their mastery resides in the synthesis of means and ends; in bringing then quite new technologies of structure and environment into such assured relationships one with the other. This synthesis was, however, not contained within the realm of technics alone, but opened up powerful new possibilities for the poetics of architecture.”

Page 18 – Image_04

“In his lecture/essay ‘Seemliness’, dated 1902, Mackintosh wrote that an architect must possess technical invention in order to create for himself suitable processes of expression – and above all he requires the aid of invention in order to transform the elements with which nature supplies him – and compose new images from them.”

“A simple four-storey block of studios occupies the northern edge of the site facing Renfrew Street.”

“The studios are lit by the unchanging light from enormous north-facing windows, in absolute conformity with the conventions of the painting studio. But circulation through the building takes on through diverse and ever changing lights and the important public rooms are invested with individual qualities through their lighting.”

Page 19

“The library (Figure 1.20), at the south-west corner of the building, is lit by three deeply incised windows in the south wall, one of which rises high to the gallery level, and to the west are three tall oriel windows that project beyond the face of the wall with widely splayed reveals. Together, these illuminate the library with the most dynamic light.”

Page 21 – image_05

“But time has passed, and practical experience has shown that… the want of appearance of stability is fatal.”

Page 22 – image_06

“The lighting of the library is dominated by the group of silver and black lamps that hang low over the central magazine table. These have coloured glass inserts that refer to the luminescent colours of the chamfered spindles of the upper gallery balustrade.”

Page 23

“Soane, Labrouste and Mackintosh”

“All of their work we see these technological means consistently applied in the service of qualitative ends, technics subservient to poetics. This is their most important contribution to the history of the architectural environment and is a legacy that can be traced throughout the work of the most significant architects who followed them.”

Page 24 – image_07

“Mies’ discussion of the design was in terms of structure and its expression”

“He was interested in the reflection of light off the envelope, not its passage into the interior of the building as an environmental service.”

“Mies offered the poetic paradox of the glass box that is not about the transmission of light.”

Page 34

“The site: a big lawn. Slightly convex. The main view is to the north, therefore opposite to the sun; the front of the house would usually be inverted… Receiving views and light from around the periphery of the box, the different rooms centre on a hanging garden that is there like a distributor of adequate light and sunshine. It is on the hanging garden that the sliding plate glass walls of the salon and other rooms of the house open freely: thus the sun is everywhere, in the very heart of the house.”

Page 35 – image_08

Page 36 – image_09

“The sides of the fireplace and the firebox itself are of brick – the only occurrence of this traditional material in the house. All of this implies that, consciously or otherwise, the force of tradition survives alongside the argument for innovation in the seminal work of the Modern Movement.”

Page 37 – image_10

Page 38 – image_11

“’Is the Tugendhat house habitable?’ Fritz Tugendhat replied: After almost a year of living in the house I can assure you without hesitation that technically it possess everything a modern person might wish for. In winter it is easier to heat than a house with thick walls and small double windows. Because of the floor-to-ceiling glass wall and the elevated site of the house the sunlight reaches deep into the interior. On clear and frosty days one can lower its windows, sit in the sun and enjoy the view of a snow-covered landscape, like in Davos. In summer, sunscreens and electrical air-conditioning ensure comfortable temperatures… In the evenings the glazed walls are hidden behind silk curtains to avoid reflexions of light.”

Page 39 – image_12

Page 44 – Image_13

“The drawing of ‘La grande sale et la Cheminée’ is vitally important in the account of the significance of the fireplace in Le Corbusier’s domestic architecture. It shows a very precise relationship between the natural warmth of the sunlight flowing through the tall window to the right-hand – north – end of the room and the almost primitive environment of the sunken cavern beneath the ramp, containing the hearth.”

Page 45

Page 46 – image_14

“In their abstraction, these images allude to the possibility of an environment in which the conventional qualities of light and shade, warmth and chill and the visible presence of the instruments of environmental provision, fireplaces, stoves, lamps are omitted in favour of an idealised, uniform environment sustained by invisible machines. In other words, a notion of environment that has cut all links with tradition, and even with advanced contemporary practice, in pursuit of a truly new vision.”

Page 48 – image 15

Translucent Shimmer

“A similarly significant influence on the development of Mies’ environmental vision may be found in the glass room project that Mies made for the Stuttgart Werkbund Exhibition of 1927. This used a variety of glass types, ranging from clear to opaque, and of varying tones. Under a uniformly illuminated ceiling of white fabric the effect was of shimmering, translucent space.”

Page 49

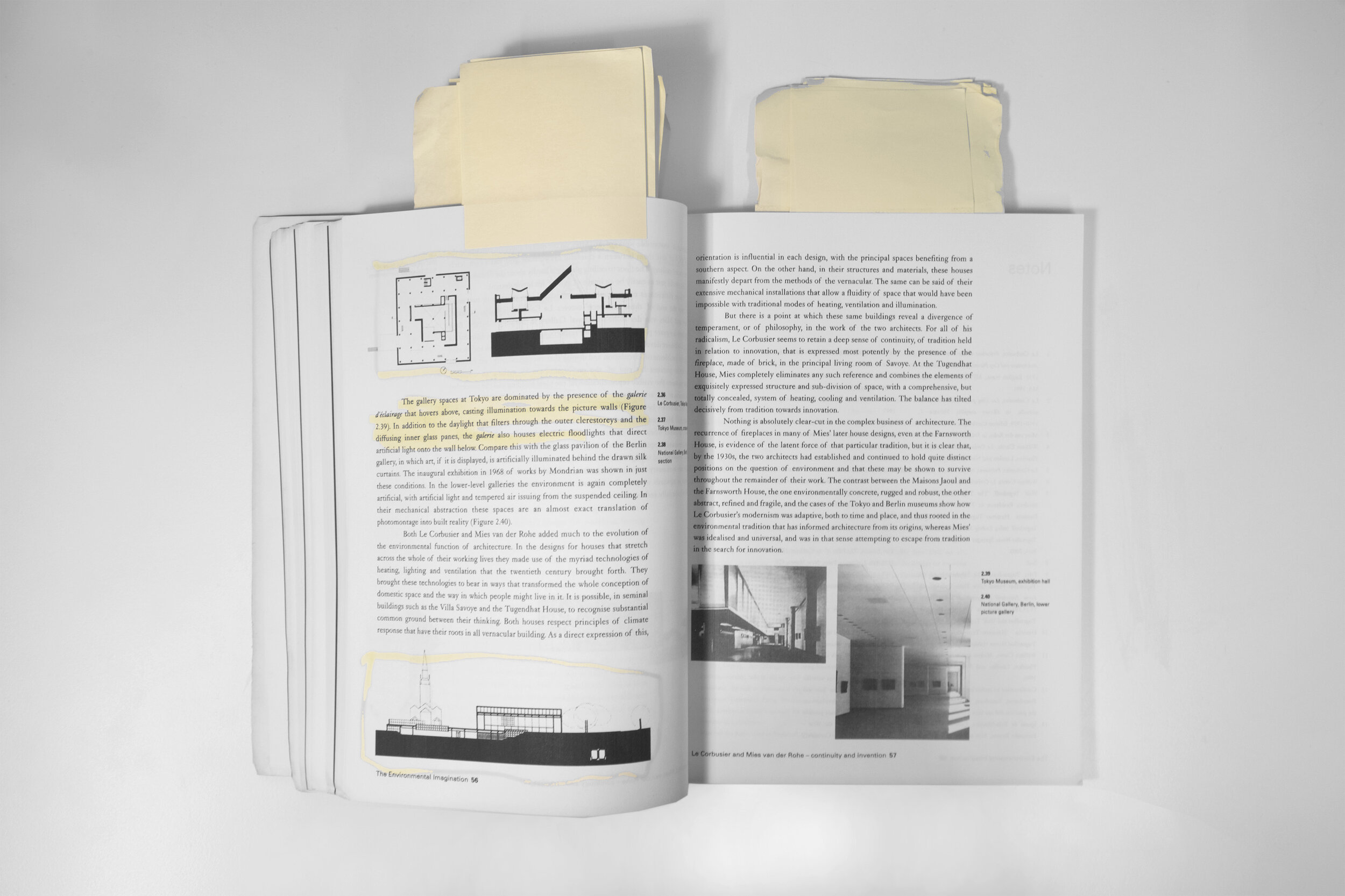

“In the post-war years the environmental aspects of the works of Le Corbusier his acknowledgement of tradition, of the natural climate as a powerful determinant of the nature and condition of the environment of a building. Mies van der Rohe emphatically embraced the potential of mechanical services, invisibly and silently to provide an ‘ideal’ and constant environment. The distinction may be characterised as designing, on the one hand, with climate and, on the other, against climate. Two brief comparative studies now illustrate the end point of this trajectory.”

“Mies’ vision of the essence of the modern house: Nature should also have a life of its own. We should avoid disturbing it with the excessive colour of our houses and our interior furnishings. Indeed, we should strive to bring Nature, houses and people together in a higher unity. When one looks at Nature through the glass walls of the Farnsworth House it takes on a deeper significance than when one stands outside. More of nature is thus expressed – it becomes part of a greater whole.”

Page 52 – image_16

“By contrast, Le Corbusier’s design for the Maisons Jaoul, built in the Paris suburb of Neuilly. 1951-1954, stands as a marked alternative to the modern dwelling.”

“The aspect of the sun dominated the lay-out of the plans and sections.”

“Rooms that are sun-filled and well-lit, easy to heat and effectively ventilated could be said to represent the victory of good sense over ideology.”

Page 53

“The gallery spaces at Tokyo are dominated by the presence of the galerie d’eclairage that hovers above, casting illumination towards the picture walls (figure 2.39). In addition to the daylight that filters through the outer clerestories and the diffusing inner glass panes, the galerie also houses electric floodlights that direct artificial light onto the wall below.”

Page 56 – image_17

NORTH LIGHT

“Curtis has argued that, throughout his career, Le Corbusier’s work was suffused by a ‘Mediterranean myth’, a preoccupation with the conditions of the south: ‘Over the years I have felt myself becoming more and more a man of everywhere but always with this firm attachment to the Mediterranean: queen of forms and under light.’”

Page 61

“Aalto’s moving ‘memoriam’, written on Asplund’s death in 1940, captured the ground that they shared, ‘the art of architecture continues to have inexhaustible resources and means that flow directly from nature and the inexplicable reactions of human emotions. Within this latter architecture, Asplund his place.”

Page 62

“The upper walls have a textured, white stucco finish that, struck by light from the windows, works as a bright diffuse reflector, distributing light evenly throughout the room. On clear days at all seasons small, quickly moving.”

Page 63

“patches of bright sunlight are projected onto the interior (figure 3.4). Even within the conventions of architectural classicism, this dynamic light transmits a sense of universal nature into the room. During the hours of darkness, and this means for much of the day in winter at this latitude, the reading room receives its primary and symbolic light from a large white glass pendant that hovers, like an inverted representation of the sky vault, above the central desk. Here and throughout the building, where Asplund designed all the light fittings, artificial lighting is an essential element of the architecture.”

Page 64 – image_18

Tracking

“The sun-filled interior speaks eloquently of Asplund’s deep sensitivity to the nature of light at this northern latitude. The stair hall is as transparent as can be. The slender mullions hardly interrupt the flow of light, the rounded forms of the encased steel columns are softly modelled, the staircase is delicately suspended from the structure and the balustrades have sparse, polished steel balusters (figure 3.8). The great hall further demonstrates Asplund’s master in organising southerly light. The rooflight is disarmingly simple, a south-facing adaptation of the conventional, industrial north light (figure 3.9). This admits a flood of unobstructed light to the northern edge of the hall. The rooflight enclosure and the ceiling and walls of the third floor are white-painted to strengthen the illumination by providing strong first reflections. This light then reaches the warmth of the Oregon pine panelling of the balustrades of the first and second floor balconies and lower walls. From these a warm glow is cast throughout the hall and the soft curves of the balcony front and the courtroom enclosures are animated by ever-changing patterns of light and shade as the sun tracks across the sky.”

Page 66 – image_19

“When you see his buildings in an urban setting you are astonished to find how much of nature’s principles he has managed to introduce into the man-made environment, how his lines vibrate with biological life and how his forms follow the complex inner requirements. Yet when you see his creations in country settings you are amazed at the amount of urban culture he succeeds in blending into the virgin landscape… The bridging over of the old gulf between man and nature, the pointing out of what they have In common, is probably the nucleus of Aalto’s alternative.”

“In considering the environmental qualities of Aalto’s works, an essential text is the essay, ‘The Humanizing of Architecture’, There, in describing the studies that he conducted during the design of the Paimio Sanatorium, he stated that, ‘Architectural research can be more and more methodical, but the substance of it can never be solely analytical. Always there will be more of instinct and art in architectural research.’”

“We find in Aalto’s work from the late ‘twenties onward an ‘attack’ whose freshness, professional rigour and technical imagination amounted to a form of significant innovation in themselves. If we take for instance his analysis and solutions to the needs of the tuberculosis patients at Paimio we find a case-study of a different order from the idealised and abstract models of functionalism proposed by his contemporaries.”

“Wilson describes how the patients’ rooms were designed in their environmental detail to ‘respond to the nervous condition and particular needs of a patient’. This intention was translated into a complex installation in which natural light, sunlight and ventilation were supplemented by specially designed light fittings and radiant ceiling heating that together constituted, ‘an unprecedented density of relevant detail to sustain the overall generation of novel form’.”

Page 68

“The main problem connected with a library is that of the human eye… The eye is only a tiny part of the human body, but it is the most sensitive perhaps the most important part… Reading a book involves both culturally and physically a strange kind of concentration; the duty of architecture is to eliminate all disturbing elements.”

“Theoretically… the light reaches an open book from all these different directions and thus avoids a reflection to the human eye from the white page of the book… In the same way this lighting system eliminates shadow phenomena regardless of the position of the reader.”

Page 69

“Aalto’s understanding of the specific qualities of the northern climate and the manner in which these might inform this ‘personal and idiosyncratic’ expression.”

“Pallasmaa has commented on the utility of the L-shaped plan when adopted in the Nordic countries, ‘deriving as it does from an attempt to respond to such conditions as basic orientation and sun, the direction of arrival, views and the opposition of public and private realms’.”

Page 71 – image_20 (note)

Cave-Tent-Cosy-Infinity

“The relationship of the fireplace-filled spine wall and south-facing, sunlit rooms is evocative of the deep traditions of domestic architecture and its response to nature.”

“This is the primary, practical heat source, but the fireplaces are the symbols of warmth.”

“This establishes a sequence of diverse, sheltered, sun-warmed places upon which the life of the house may extend to enjoy the precious benefits of the sun as it slants in at the low angles of this northern latitude. One can imagine the Aaltos on long, light summer’s nights lingering late in the fire-lit covered terrace; almost recreating the conditions of primitive shelter.”

Page 72 – image_21

“We begin the discussion by considering the configuration and geometry of this remarkable composition. In his essay, ‘The Dwelling as a Problem’, Aalto wrote, a dwelling is an area which should offer protected areas for meals, sleep, work, and play. These biodynamic functions should be taken as points of departure for the dwelling’s internal division, not any out-dated symmetrical axis or ‘standard room’ dictated by the façade architecture.”

Page 76

Necessity into Poetry

“By creating this artificial ground level, open to the sky at the centre of the plan, Aalto reduces the obstruction to the sun on the south and west sides of the courtyard, thereby bringing the glazed cloister of the administrative wings barely obstructed sunlight for much of the day. The 10o slope of the library roof, when projected across the courtyard, almost exactly intersects the meeting of the ground and the cloister wall opposite, guaranteeing that the glazed cloister will be filled with sunlight in the depth of the Finnish winter.

“The library, which is also entered from the courtyard, occupies the whole of the south-facing block, where it is illuminated by the sun all day long through its tall, timber-mullioned windows.”

“The image of the roof trusses in the Council Chamber at Saynatsalo is one of the most familiar in the whole of twentieth-century architecture (Figure 3.33). These have been interpreted variously as ‘upturned hands’ – Porphyrios – or as an evocation of a ‘great barn’ – Quantrill – but they have significant environmental function in allowing, by supporting the secondary roof framing, unrestricted ventilation between the interior and exterior surfaces of the double roof construction that is necessary in Finland’s winter climate. This may be ‘prosaic’, as Richard Weston suggests, but a crucial part of Aalto’s genius was his ability to transform necessity into poetry.”

Page 79

“Natural or artificial, is absorbed by the dark brickwork, rendering the room mysterious rather than functional. Juhani Pallasmaa has written that, ‘the dark womb of the council chamber… recreates a mystical and mythological sense of community; darkness strengthens the power of the spoken word’. Set against the luminosity of so many of Aalto’s interiors, this is a surprising, space detached from external nature, bringing intense focus to the functioning of local democracy.”

“Aalto’s metaphor of ‘The Trout and the Mountain Stream’ referred specifically to the evolution of ‘architecture and its details’ as biological analogy. But the idea of deep immersion in a stream – a habitat – also serves to define Aalto’s own relationship with his habitat in the nature – the environment – of Finland. The outcome is an architecture absolutely of its time and place, but one that achieves a unique synthesis of ends and means – truly an alternative environmental tradition.”

Page 80

“But Kahn was also the great ‘poet’ of late twentieth-century architecture and the essence of that poetry may be found in his deep preoccupation with light – natural light – and its complex inter-relation with the form and materiality of architecture.”

“A room is not a room without natural light”

“A great American poet once asked the architect, ‘What slice of the sun does your building have? What light enters your room?’ – as if to say the sun never knew how great it is until it struck the side of a building.”

Page 87

“A man with a book goes to the light. A library begins that way.”

“Exeter began with the periphery, where the light is. I felt the reading room would be where a person is alone near a window, and I felt that would be a private carrel, a kind of discovered place in the fold of the construction. I made the outer depth of the building like a brick doughnut, independent of the books. I made the inner depth of the building like a concrete doughnut, where the books are stored away from the light. The centre area is a result of these two contagious doughnuts; it’s just the entrance where the books are visible all around you through the big circular openings. So you feel the invitation of the books.”

Page 95

“As Kahn said, ‘Exeter started with the periphery, where the light is.’”

Page 96

“This ‘natural lighting fixture’… is rather a new way of calling something; it is rather a new word entirely. It is actually a modifier of the light, sufficiently so that the injurious effects of the light are controlled to whatever degree of control is now possible. And when I look at it I really feel it is a tremendous thing.”

Page 98

When I’m closest to human beings.

“Another function of the courtyards, that is only apparent by direct experience of the building, is to allow the visitor to enjoy the natural climate as an alternative to the necessarily controlled conditions of the galleries. Beneath the vine-covered wires that criss-cross both the fountain court and the north court – used as an outdoor extension of the cafeteria – the warmth of the sun and gentle breezes may be experienced. Here, just as in the relationship of the natural and mechanical environments of the laboratories and study cells at Salk, Kahn subtly connects the museum environment to nature. The boundary between the two environments can be modified, if needed, by the use of external blinds of fine woven steel mesh.”

“The daylight control device of the museum section is modified to support artificial lighting troughs that span laterally and the arched gables, sheltered by the adjacent bays to north and south, are fully glazed. The result is to provide a general distribution of illumination that is modulated by the special events of the glazed gables and the continuous strip glazing at floor level to the east. In a way Kahn has, again, taken the book to the light.”

Page 100

“When a man says that he believes natural light is something we are born out of, he cannot accept a school which has no natural light. He cannot even accept a movie house, you might say, which must be in darkness, without sensing that there must be a crack somewhere in the construction which allows enough natural light to come in to tell how dark it is. Now he may not demand it actually, but he demands it in his mind to be that important.”

“Robert Venturi criticised this building because, in his opinion, it is not clear whether the light is natural or artificial. But that would seem to miss the point. Kahn’s aim was precisely to transform natural light into a medium in which art works might be ‘re-viewed’, in a way that is different from that of the traditional day lit gallery and certainly that is different from the absolute uniformity of artificial lighting; as he insisted, ‘light is the theme’.”

Page 101

Page 102 – image_22

“Shortly after Kahn was appointed to design the building, he made a visit, with Professor Jules David Prown, the Mellon Center’s first Director, to Mellon’s houses at Georgetown, Washington, Dc, and to Upperville, Virginia. The object was to view Mellon’s collection of paintings in their extant setting. By all accounts, the experience of art in the setting of Mellon’s house made a big impression on Kahn. Between book, painting and drawing – this is the room-like quality of the collections’. Kahn and Prown also visited the Philips Collection that is exhibited in a large house in Washington. On these grounds the building at New Haven may credibly be interpreted as a translation of the domestic into the institutional. But, in addition to the specific influence of Mellon’s house, it is also possible to see something of the grand English house in the configuration of qualities of the building. Many of the paintings in Mellon’s collection were created to be hung in the rooms of such houses, both in the city and the country, and the galleries of the Mellon Center convey something of the quality of these rooms. In the great houses of England, these paintings are viewed in both grand ceremonial spaces and rooms of intimate scale.”

“His rooflight design, with its multi-layered system, of a solar control and diffusion, simulates the gentle quality of English light that is both found in English buildings and is depicted in the paintings themselves. Whether we consider the great first floor courtyard or the smaller perimeter galleries, the building has the quality of a great house rather than of an institution (Figures 4.37-4.39).”

Page 103-104

Fresh-Modelling-Warm

“Kahn makes a subtle, but crucial differentiation between the two courtyards. The tall entrance court is not used to exhibit paintings from the collection. It is therefore, freed of the obligation to provide strict light control. The omission of louvres and diffusers floods the space with vibrant light and this animates the controlled environment of the upper galleries that overlook it. Although much critical attention has been given to the rooflighting system, it is important to note that, in many respects this is a window-lit building. The complex disposition of window opening in the facades is, in accord with functionalist principles, a direct expression of the location and lighting needs of the rooms within, in the upper galleries, the combination of window and rooflight sustains the illusion of the house as art museum.

Page 105

“A measure of the significance of an architect’s work is the extent to which it reveals principles that add to the body of knowledge that defines and informs the discipline of architecture. Kahn’s idea of ‘served’ and ‘servant’ long ago achieved that status. But it is important to realise that this is more than a technological distinction between incompatible elements. These buildings show that, without abandoning faith in the modern movement’s clarification of architectural language, it is possible to organise ‘served’ and ‘servant’, to mould form, material, light and the other environmental qualities to profoundly expressive ends. Kahn’s overriding faith was in architecture itself and that was the source of his method and achievement. ‘You realise when you are in the realm of architecture that you are touching the basic feelings of man and that architecture would never have been part of humanity if it weren’t the truth to begin with.’”

Page 107

“The environmental priority in such a climate would be to achieve comfort – coolness – during the hot months with winter warmth being a secondary, but not unimportant concern. This view is supported by Holberton who observes that Palladio’s villas were conceived to be occupied from spring, ‘since it was cooler and more salutary out of town during the heat of mid summer’, until late autumn, when the harvest and hunting seasons were finally over.”

“Writing about Scarpa’s architecture, Francesco Dal Co has observed: ‘The sensitivity Scarpa reveals in, for instance, his treatment of light and its handling of colour tones is the outcome of… his profound affinities with Venice.”

“Sergio Los further expanded on this theme:

One compositional technique introduced by Scarpa may, I think, be derived from the architecture of the towns of the Veneto. For this purpose it is sufficient to recall Scarpa’s projects of the 1950s, with their corner windows… He translated the corner-windows of the new spatial concept into the vocabulary of the Veneto.

The light produced by the corner-windows becomes a chromatic luminosity full of transparency, typical of the region’s visual arts for centuries… His rooms have a luminosity which, apart from the manifestly different vocabulary generates the flowing light of Palladio and his 17th and 18th century successors.”

Luminosity

Page 112

“Other commentators have also illustrated the key role that is played by light in Scarpa’s work. Boris Podrecca writes:

In Scarpa’s work it is not just the physical presence of things that transfigures tradition, but also the light, which is a lumen not of tomorrow but of the past – the light of the golden background, of the glimmering liquid of the ivory- coloured inlay, of luminous and shimmering fabrics recreated in marble. It is the light of a reflection of the world.”

“Scarpa expressed the nature of his approach when he said, ‘I really love daylight: I wish I could frame the blue of the sky!’ Sergio Los has written at length about the narrative function of light in Scarpa’s approach to the display of Canova’s sculptures, ‘bringing them to light’.”

“It is precisely the light that shows the illuminated sculptures and ‘translates’ Canova, giving them a new interpretation and constituting – together with the organisation of space and construction – the typological content of the museum.”

Page 113

“The diurnal symmetry of the light is quite different from that of a basilican church, where the east-west orientation demanded by Christian orthodoxy creates a strong contrast between north and south aspects. Here the uniformity of the light emphasises the geometrical axiality of the space. Scarpa’s light couldn’t be more different. From the vestibule of the basilica the eye is led into a dazzling white volume in which sculptures are freely disposed in a complex field of light, some in silhouette, others brightly illuminated.”

“As Sergio Los has observed: Each statue has a very precise place, with respect to the overall space and to the light that pours in – at times with glaring violence, at other times softly and faintly – modelling the plasters on display, modifying them over the course of the day, with the changing seasons and the variations in weather.”

Page 114

“Scarpa’s invention of the trihedral corner windows, simultaneously window and rooflight, that illuminate the ‘high hall’ is, environmentally and tectonically, the most remarkable element of the building (Figure 5.4). To the west.”

“Their configuration admits light from all orientations and, unlike a conventional window set within a wall, casts light across the walls themselves. This apparently simple device is the source of the magical quality of light that binds art and architecture into a complex unity.”

“These images demonstrate the variety of conditions under which the sculptures are simultaneously illuminated (Figures 5.3 and 5.4). George Washington is strongly modelled by direct sunlight, ‘Amor and Psyche and butterfly’ stand in relative shade, against the projection of the light of the corner window upon the wall, and the bust of Napoleon is softly modelled against the shadow by reflections transmitted from the adjacent sunlight wall (figure 5.5).”

Page 115 – image 23

“In his 1976 lecture, Scarpa spoke of the issues behind the conception of this arrangement: I wanted to give a setting to Canova’s ‘The Graces’ and thought of a very high wall: I set it inwards because I wanted to get the light effect of a bay. That sort of dihedron getting into the room produces that fineness of light which makes that point as well-lit as the other walls.”

“By rejecting the implicit technological expectations of mid-twentieth-century building, with its extensive apparatus of environmental services, Scarpa is able to focus on the fundamentals of the architectural environment. The ambience of the interior, luminous, thermal and acoustic, is the direct product of the interposition of the enclosure within the ambient climate. In this way, whatever the consequences in terms of modern notions of environmental comfort, there is an absolute unity of the internal environment in all its dimensions. This building is a supreme instance of the environmental imagination.”

“On entering the castle from the street, one’s first impressions are of the transition from the brightness and bustle of the street, as one passes over the timber drawbridge, through the archway and into the courtyard. Arriving in the shadow of the fortified wall, the sounds of footsteps on white gravel paving and, then, of running orderly environment. The gravel paving is bright, almost glaring in the sunlight. The green hedge that defines the boundary between the gravel and the lawn beyond almost instantly moderates this effect. The façade of the museum faces almost due south and, on the abundant sunny days of Verona, is brightly lit with strong shadows cast in the deeply modelled loggia. The recess of the Cangrande statue to the left is also deeply modelled with a complex rhythm of light and shade.”

Page 116-117 – image_24

“Moving towards the entrance of the museum, the visitor passes from the irregularity, brightness and looseness of the gravel paving to the firmer platform of the stone paving. The ‘threshold’ between the two surfaces is marked by a drinking fountain to the left, with its stepping stone set in the slightly agitated pool, and the calm, shallow pool to the right that lies in front of a larger fountain. As one proceeds towards the entrance, the pavement is poised between the inaccessible water to the right and the open space of the lawn to the left. Proceeding further towards the entrance the detail of the wall of the ‘Sacello’ made from Prun stone, standing to the left of the entrance becomes visible. The entrance itself is declared by the projecting, steel-framed, concrete wall that leads one into the interior. In comparison with the exterior, the interior presents a strong contrast of all three environmental elements: thermal, visual and acoustic. The entrance hall is dark, but adequately lit, cool, but comfortable and quiet. This allows the visitor to adapt in preparation for entry to the ‘enfillade’ sequence of the ground floor sculpture galleries to the left. Standing at the threshold of the first gallery spaces, with their careful differentiation of old fabric and new surfaces, are relatively dimly lit, with the array of sculpture modelled by light that enters from the, as yet, unseen windows to the left-hand, southerly side of the building (Figure 5.10). At the end of the axis, the lower part of the Cangrande space is seen though a characteristic Scarpa metal grille. The strongly directional quality of the light is enhanced by the texture of the plaster and neutral colour of the walls and the lateral banding of the marble and slate floor. The darker tone of the smooth plaster ceiling adds to the calmness of the space and focuses attention on the human0sized territory defined by the sculptures. The serenity of the space is reinforced by the contrast of its coolness on a hot summer’s day. Moving on into the first gallery, attention is immediately drawn to the south, where the cavern-like interior of the ‘Sacello’ stands beneath the gothic arch of the clerestory (Figure 5.11). The clerestory brings light into the principal volume and strongly models the sculptures there. The ‘Sacello’ contains light of an entirely different nature. Its black plastered walls and dark brown clay- tiled floor are strongly illuminated by the flood of light that enters through a full-width roof light, creating a strong contrast with the calm light of the main gallery. From the gallery the clerestory frames a view of the tower above the entrance to the courtyard. The juxtaposition of vertical and horizontal light powerfully reinforces the distinction between the two spaces. Scarpa’s intentions for the lighting of the Sacello in relation to the main gallery were stated with absolute clarity in the sketches that he made during the development of the project. In this linear sequence of spaces, the location and orientation of the individual sculptures Is absolutely integral with the entire architectural composition. These occupy the ‘light field’ in a manner that reveals and interprets their individual qualities as works of art, but which, reciprocally, demonstrates the character of the architectural space through the inter-relation of material, form and light. Most of the sculptures stand freely in space, but a small number are precisely located. For example, the ‘Madonna Incoronata’ and the ‘Madonna con Bambino’ in the third space, are placed in specific relationship to the architectural intervention of the steel framed, blue and red plastered screen that stands in front of the north wall of the space (Fogire 5.12). By its dimensions, material and position, this screen reconstructs the nature of the spaces and its light and thereby emphasises the significance of these quite small sculptures. The qualities of these rooms and of the works displayed in them support Sergio Los’ hypothesis, made with particular reference to the Canova Gipsoteca, ‘The architect makes room for the sculpture and places them in the correct light, in such a way they ‘constitute’ the space which they occupy.”

Page 118-120 – image 25

“As at Possagno, his masterly manipulation of daylight is a primary element in the presentation and interpretation of the works of art that it houses and in the parallel narrative on the building itself.”

Page 121

“The office building is, perhaps, the most ubiquitous building type of the twentieth century. The accommodation of the prosaic functions of commerce and administration has led to the evolution of a technologically based building type, in which utility and consistency are usually given priority over poetry and diversity. Cities throughout the modern world are dominated by these structures providing identical environments for identical functions and representing the triumph of globalisation over local identity.”

Page 123

“All these buildings demonstrate Scarpa’s acute sensibility to the environmental dimension of architecture. This sensibility is founded upon his understanding of the potentiality of the historical precedents, of both vernacular building and the high architecture of Palladio, as models for contemporary design in the climate of the Veneto.”

Page 126

“One of the most remarkable attributes of human vision is our ability to see in levels of light that vary from the darkness of a moonless night to the vivid glare of a sunlit summer’s day.”

“The construction of a building enclosure inevitably limits the range of illumination that exists under the open sky. The amount of light that enters an interior is determined by the size and position of the windows nad rooflights and the reflectance of the materials that line internal space.”

“St Mark’s at Bjorkhagen near Stockholm (1956-1964) and St Peter’s at Klippan (1962-1966) Colin St John Wilson has observed: Instead of the coloured radiance of the Gothic or the dazzling luminous white of the contemporary tradition from the Bryggman to Leiviska, we are invited into the dark. Enveloped in that heart of darkness that calls on all the senses to measure its limits, we are compelled to pause. In a rare moment of explanation, Lewerentz stated that subdued light was enriching precisely in the degree to which the nature of the space has to be reached for, emerging only in response to exploration. This slow taking possession of space (the way in which it gradually becomes yours) promotes that fusion of privacy in the sharing of a common ritual that is the essence of the numinous. And it is only in such darkness that light begins to take on a figurative quality – the living light of the candle flame or as at Klippan, the row of the roof lights which forms a Way of Light between sacristry and altar.”

Page 129

“Psychologist Richard Gregory suggests: It might be said that moving from the centre of the human retina (cones) to its periphery (rods) we travel back in evolutionary time. From the most highly organised structure to a primitive eye which does no more than detect simple movements of shadows.”

“The eye is the organ of separation and distance, whereas touch is the sense of nearness, intimacy and affection. The eye controls and investigates, whereas touch approaches and caresses. During overpowering emotional states, we tend to close off the distancing sense of vision; we close our eyes when caressing our beloved ones. Deep shadows and darkness are essential because they dim the sharpness of vision, make depth and distance ambiguous and invite unconscious peripheral vision and tactile fantasy.”

Chapel of Resurrection, Stockholm (1923-1925)

Page 130

“Ahlin offers the following description of this sequence: The mourners would wait along the shaded north side. They were then led in through the portal, turning their attention to the east, toward the sunrise. At the ceremony’s end they would go out through a lower door which opened up on the landscape to the west. Here the ground was sculpted out to a lower level and the pine trees were sparse. Light flooded in, the field of vision was opened out and one’s pupils would contract. One’s gaze returned to the living.”

“This analysis reveals Lewerentz, precisely manipulating the potential of visual adaptation, from shaded exterior, to controlled, subfusc, directional interior, finally to temporary glare and rapid adjustment to the full light of the forest clearing.”

Orientation – Depth – Material – Part L Construction

Page 131

St Mark’s Church, Bjorkhagen, Stockholm (1955-1964)

Page 132 – image_26

“On entering the church the darkness is first tempered by the presence of the arrays of polished copper and brass light fittings that float in the space. These provide artificial illumination to supplement that from the windows, adding an additional element to the visual field. Small candelabra and carefully sited spotlights bring yet more diversity of light, as do the glittering gilt and silver of the cross and candlesticks that adorn the alter.”

Page 134 – image_27

“This is a continuation of Lewerentz’s sensibility to the nature of human sight that was shown in the chapel of the Resurrection.”

Page 135 – image_28

“In contrast to the brightness that prevails in so much architecture of modern times. The literal and metaphorical darkness of this building uncannily makes the nature of light more apparent.”

Page 139 – image_29

Measure Light

“Lewerentz’s life’s work.”

“Most particularly they teach us that this environment is a complex overlapping of sensations, of natural elements, particularly of light and mechanical provisions, of all-enveloping warmth in the cold of the northern winter and of subtle acoustics. Quantitatively and qualitatively these sensations change almost imperceptibly as time passes and as our bodies and minds assimilate and respond to the rich ambience of the spaces that Lewerentz created.”

Page 140